Nambu World: Teri Visits the WWII

Battlefields and Caves of

Introduction

I visited

Two things

that are everywhere on

Several covered shopping arcades lead south from Kokusai-dori and offer even more of the local souvenirs and specialties, including local fruit and sugar cane.

I had taken

an early flight out of

The drizzle

turned into a downpour, so I didn’t spend long at the castle the first day. I

went back on my last day, when it was dry, and took this picture. The castle

was the home of the Okinawan kings. Okinawa had a rather ambigious

status and paid tribute to both

There were performances of traditional music and dance being staged on the grounds.

Just down the road from the castle are the

royal tombs. The actual chambers were closed when I was there due to the threat

of rain.

Nearby I took this shot of an orchid.

Now the Military Stuff…

My main

reason for going to

Orientation Maps

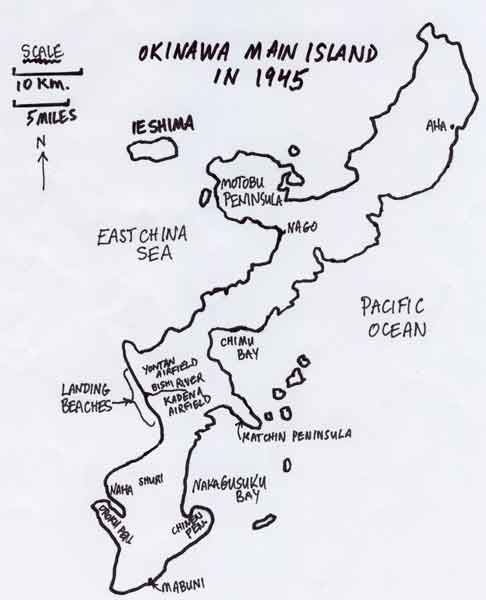

Here are

two maps. I traced these and then hand-labelled them, so they are not that pretty,

but they should help to keep track of where the paces are that I am describing.

This first one shows the whole

Here’s a map of the southern part of the island showing places I visited.

I visited

this area on my last day on my own after taking a local bus to Kadena, but I am putting it first here since it was the

beginning of the land battle. I got off the bus just north of the

Towards the sea the

banks of the

Kakazu Ridge

Kakazu Ridge was the first stop on my tour with Mr. Majewski. This ridge is a few kilometres north-east of

The highlight of this stop for me was the chance to examine a Japanese pillbox/machine gun emplacement. Here it is from the front.

This is the back. The entrance is the

small square hole at the bottom. Originally it would have been a bit more

accessible, but the dirt has washed down into the entrance way over the years.

Of course I couldn’t resist the chance to go inside. Here I am looking out one of the firing ports. My hair is a mess, but I had to crawl through a muddy hole to get in, so I don’t look that bad considering (fortunately you can’t see my muddy jeans).

This is the right firing port viewed from the

inside (the left one when viewed from the front).

Here is the left firing port (the

right one when viewed from the front). The little notches below the port were

for the legs of the machine gun stand, I think. The whole thing was maybe about

eight feet by eight feet inside, if I remember correctly.

Hacksaw Ridge

This is just southwest of Kakazu Ridge. This photo was taken looking north. Kakazu Ridge is the green hill in the centre

of the photo. If you run your eye upwards from the red roofs in the lower right

quadrant you can just barely make out the bluish tower I referred to above. It

is a low tower and looks like a tiny little bluish oval here.

On Kakazu

Ridge we entered a couple of caves used by the Japanese in the war. Here is the

very inconspicuous entrance of the first of these, just behind/to the right of

the bundle of vines.

Here is Mr. Majewski

leading the way. Many of the caves started out as natural caves and then were

enlarged by the Japanese. The work was done using just hand tools, largely by

conscripted Okinawan and Korean labour. During the

war the caves usually had wooden bracing. The rubble on the floor is from bits

of the roof and walls that have collapsed over the years. The rock is quite

soft, a kind of porous limestone.

Since the footing is treacherous,

one is tempted to brace oneself by putting one’s hands against the wall, but

you have to be careful. There are lots of these huge centipedes in the caves.

They can be up to six inches long and inflict a very nasty, though usually not

fatal, sting.

This is the rear entrance of the

cave, which goes right through the ridge. Besides offering protection from

bombardment, the caves allowed the Japanese to move back and forth between the

front and rear slopes of

Although

not run by the

Sugar Loaf Hill

Further to the south-west is Sugar Loaf Hill. Today a large part of it (the left side in the photo) has been removed to make room for a shopping centre with a Duty Free Store and there is a water reservoir on top of what is left.

Here is the view from the top. The shopping centre is on the left. The Americans took thousands of casualties to get to the spot where this photo was taken. Nowadays there is a staircase, so it is a lot easier.

This small plaque is all there is to remind one of the fierce battle that was fought there.

Lt. General Buckner Memorial

On the

second day our first stop was the memorial to Lt. General Simon Bolivar

Buckner, Jr. He was the highest ranking

The memorial is located where he was killed while observing in action a unit that he planned on using later in the final assault on the Japanese main islands. The actual spot where he was standing is in the right of the photo, just down from the raised area.

The plaque is up on the raised area, a few feet from where he was standing.

This is the actual spot where he was standing. A Japanese artillery shell hit the large rock in the left of the photo and a fragment fatally wounded the general.

Just before

you mount the stairs to the raised area of the Buckner Memorial there are two

other memorials to fallen American officers. The memorials to Colonel Edwin May

(left) and Brigadier General Claudius M. Easley were originally located at the

spots where they were killed, but when Okinawa reverted to

Our next

stop was the southernmost tip of the island,

Himeyuri Heiwa Kinen

Shiryokan

Himeyuri, literally “lily of the valley”, is the

term applied to the young Okinawan girls who served as nurses for the Japanese

forces. They were from elite girls’ schools and had to perform their duties in

cave hospitals under horrifying conditions, doing things like sneaking out in

the dark to dispose of amputated body parts during lulls in the bombing. Later

when the Japanese retreated they were simply abandoned to look out for

themselves, some of them taking grenades along so they could commit suicide

(due to Japanese propoganda they feared rape and

torture if captured by the Americans). The

museum often has one of the survivors present to discuss her experiences.

Besides artifacts and a reproduction of a cave there is a hall with photos of

most of the girls. The full name of the place means “

The museum is located by one of the caves where they served, but it is not open to the public. The cave mouth, located just behind the barrier in this photo, is the site of various memorials.

Memorial of the Souls

On the

coast south of Himeyuri is the Heiwa sozo no mori koen, “Peace establishment

The coastline here is also quite scenic.

This is a rather large museum in Mabuni that does not mince words about the poor treatment of the Okinawans at the hands of their Japanese “defenders”, although there is also a noticeable anti-American slant to some of the exhibits, particularly those regarding the post-war Occupation. Unfortunately a large display of weapons and other artifacts is just thrown in a big pile to slowly rust away.

Outside the museum is a large area of monuments to the dead, with special sections for the dead of various prefectures, military units, etc. This is the memorial to the dead of the Japanese 62nd Division.

This one commemorates the dead from

Walking a little further takes one to Mabuni Hill, the site of the last of the headquarters the Japanese established as they gradually retreated south. Here is the view.

This memorial commemorates to place where Lt. General Mitsuru Ushijima and Major General Isamu Cho, the two top Japanese commanders, took their lives in June, 1945 when it became obvious all was lost and the end was only hours or days away.

This gap leads down to the entrance to the Mabuni headquarters cave.

This is another of the entrances to the

headquarters complex. It is blocked with a grill, but I stuck my camera through

for this shot.

This is believed to be the actual spot where the Japanese commanders committed suicide, although there is some doubt since the bodies had been moved when they were found. We had to clamber over some barriers and go near the cliff’s edge to get here.

On the path down the hill there are monuments to

various groups. This one commemorates the “Blood and Iron for the Emperor”

youth group (Tekkestsu kinotai).

The infamous “spring of

death” referred to in the book “The Battle for Okinawa” by Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, the third in

command, who survided the war. It was nicknamed this

because the Americans had set their artillery pieces on it and shelled it

frequently. The Japanese had to choose between dying of thirst for sure or

running a high risk of dying to fetch water. Recently the huge piece of rock

you see just inside the rope barrier fell off the overhanging cliff, adding a

more modern motivation for the moniker.

44th Independent Mixed

The headquarters cave of the 44th

Independent Mixed Brigade is near the coast north-east of the

Inside this entrance was a huge

chamber with the remains of a room on the right. I had to lighten this photo

quite a bit to make things visible. It’s dark in these caves! That’s Mr. Majewski in the white shirt with the flashlight.

Here is one of the passages. I think Mr. Majewski is about 5’7” tall, which gives you an idea of the

height of the passage.

Here is a room in the cave, probably for an

officer.

Just outside is a machine gun emplacement.

Underground Naval Headquarters

This museum

is located in the

Here is the layout of the headquarters complex.

This was the operations room. The marks on the walls are labelled as having been caused by grenade fragments when the occupants committed suicide, however Mr. Majewski sees some discrepancies in this account, such as the lack of fragments in the ceiling, among other things.

This is one of the passages in the complex.

The commanding officer’s room.

Two days turned out to be a very short time to revisit the history of those fateful months, but it was my first time to see one of the actual combat zones of the Pacific Theatre, so it was very memorable for me. I hope this short account has brought back memories to those who have been there before, and stimulated the interest of those who have not yet visited.

Last modified: March

29, 2006.

All contents are copyright

Teri and may not be used for any other purpose with prior consent.

To see my review of

Japanese Military Museums, please click here: Nambu

World: Military Museums in Japan

To return to the Nambu World main page, please click here: Nambu World Home Page