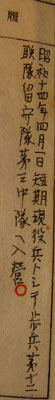

Hokobukuro

(Service Records Bags)

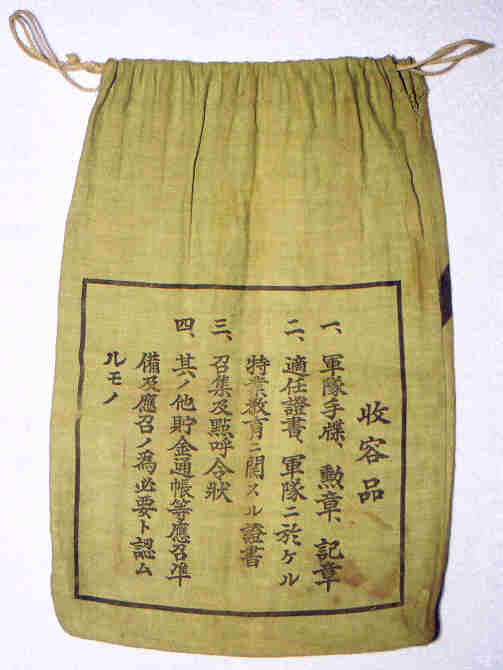

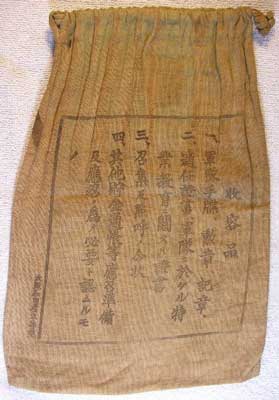

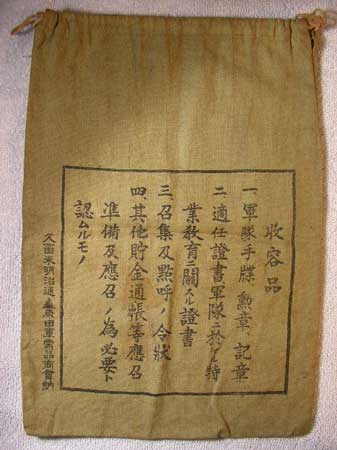

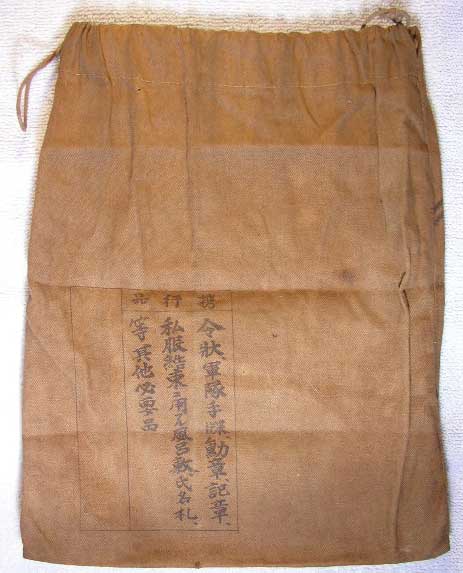

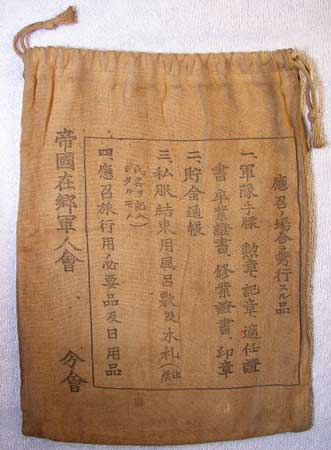

This is the bag in which a soldier

carried everything related to his service, from his call-up letter and

qualifications to decorations and campaign medals (see full list below). This

one seems to be made of cotton and is about 9” by 13” (23cm by 33cm) with a

drawstring at the top. I believe it to be a late variation, and it seems to be

the most common type. The large characters in the middle read from top to

bottom and say ho-ko-bukuro. Hoko means “public service”, and fukuro or bukuro means “bag”. The box in the lower left is for the soldier’s

name (see close-up below) and there is what seems to be a manufacturer’s logo

just below the column of large characters (see close-up below). These bags are

often mistakenly called “comfort bags”. The comfort bag was a special bag

labeled imonbukuro and was used for

gifts from home (see separate section). Hokobukuro

are also often called “personal bags” or “ditty bags” on eBay.

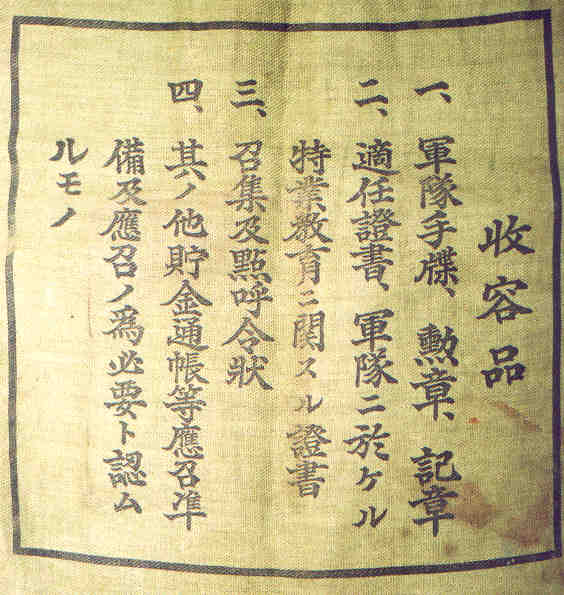

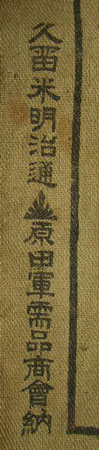

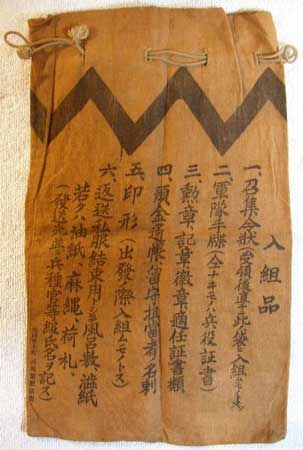

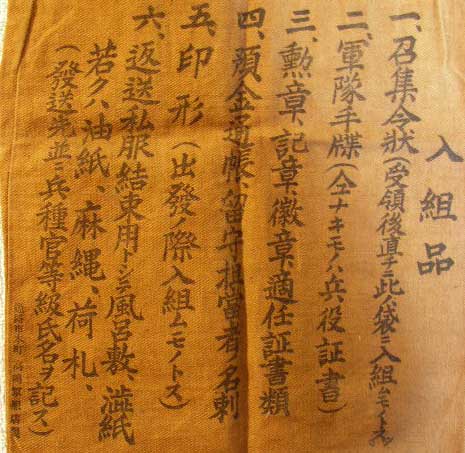

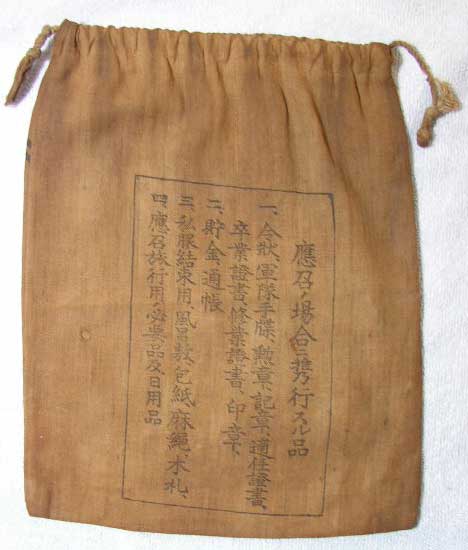

Here is the back. The writing in the box is a

list of what is supposed to go in the bag and is translated with the close-up

below.

This close-up of the label reads

from right to left, top to bottom. The far right column says shu-yo-hin, or “contents”. Here is the

rest, line by line. The numbers are the four kanji characters 1 to 4 that

appear at the top of the second, third, fifth and sixth columns from the right.

1. Gun-tai te-cho, kun-sho, ki-sho

(military handbooks, decorations, medals).

2. Teki-nin sho-sho, gun-tai ni

okeru toku-gyo kyo-iku ni

3. Sho-shu oyobi ten-ko rei-jo

(mobilization or call-up order).

4. Kono ta cho-kin tsu-cho nado o-sho jun-bi

oyobi o-sho no tame hitsu-yo to mitomuru

mono (Other things such as savings record books, etc., and things

related to preparation for the draft or recognized as needed for the draft).

This is a close-up of the logo

beneath the main characters on the front. It is probably a manufacturer’s logo.

The three characters in the circle read from top to bottom and say yamato-gokoro, or “Japanese heart (i.e.

spirit)”.

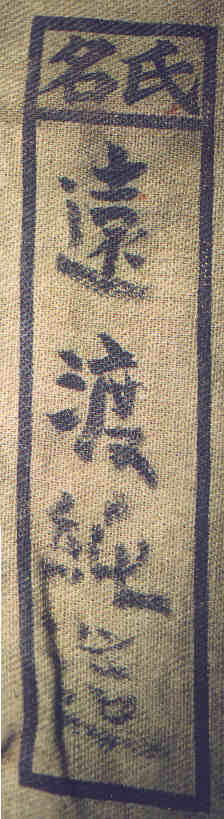

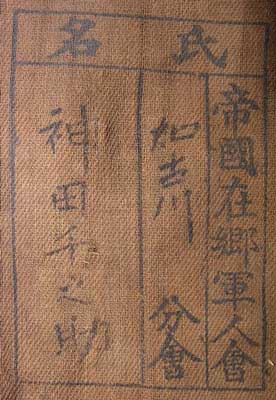

Here is a close-up of the name box

from the lower left corner of the front. The two characters in the little

sub-box at the top read from right to left and say shi-mei, or “name”. The four

handwritten characters are read from top to bottom and indicate the soldier’s

family name and given name: En-to Jun-zo.

En-to (or possibly En-do) is the family name and Jun-zo is the given name.

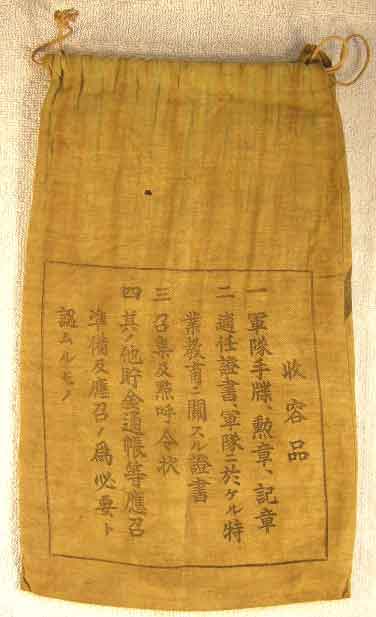

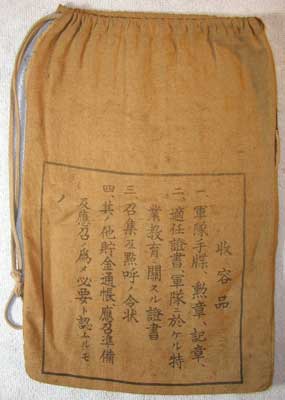

This is another hokobukuro of the same type as the previous one, which seems to be

the most common type, but with this one I actually got two of the items that

were in the bag: the guntai-techo

(military handbook) and the chokin-tsucho

(savings passbook). All were named to the same person, Mr. Kusui Ichiro (Kusui

is the family name, which the Japanese write first).

This one has the same list of stuff on the back

as the previous bag,

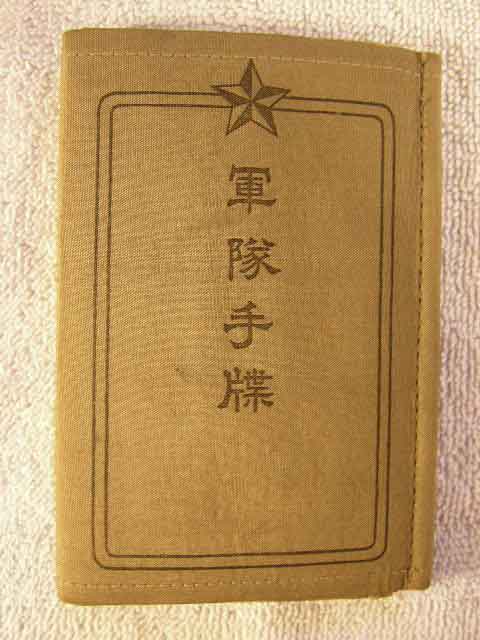

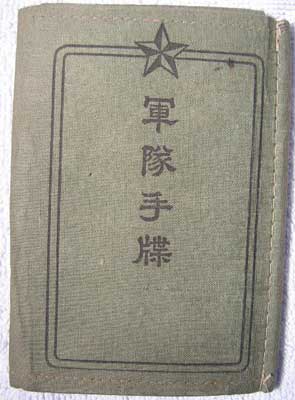

Here is the guntai-techo,

or military handbook. It is about 3.5” wide, 5” high and 5/16” thick (8.5cm by

12.5cm by 0.8cm).

This is the back with Mr. Kusui’s name in the

box in the lower left corner.

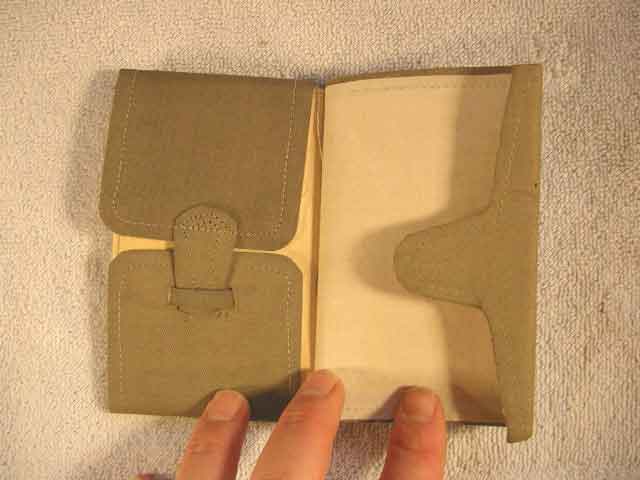

It has several tabs to keep it closed.

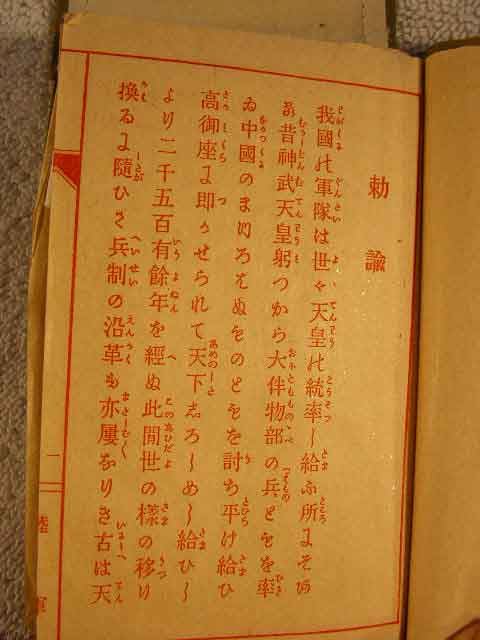

The first 30 pages (some blank) are in red with

Imperial rescripts (chokuyu). The

first and longest of these is the Meiji Emperor’s famous Imperial Rescript to

Soldiers and Sailors of January 4, 1882. It focuses on the five virtues of a

soldier: loyalty (chusetsu),

bravery/valour (buyu), righteousness (reigi), faithfulness (shingi)

and simplicity/frugality (shisso).

This document is famous enough that I can find a ready-made translation, which

I will post here. This is followed by the less well known Imperials Rescripts

to Soldiers and Sailors of the Taisho Emperor (dated July 31, 1912) and the

Showa Emperor, i.e. Hirohito (dated December 28, 1926). These are quite short

so if I don’t find a ready-made translation I will just translate them myself.

After this there are a couple of pages in black type explaining what the guntai-techo is, then the soldier’s

records.

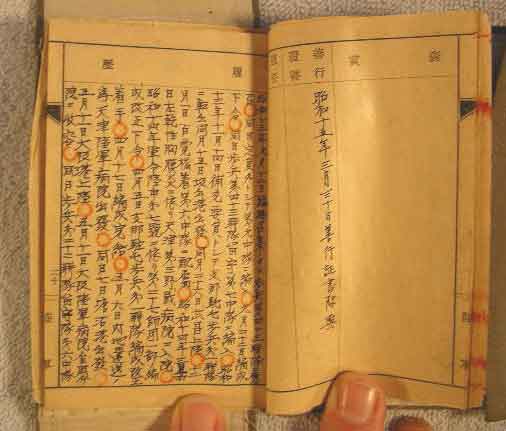

Mr. Kusui was born on June 12, Taisho 5 (1916).

He was from Mie prefecture and served in the 43rd Regiment (rentai), force remaining behind (rusutai), 7th Company (chutai). He was called up on September

12, 1938 and was discharged on March 30, 1940. I will translate the rest as

soon as I can.

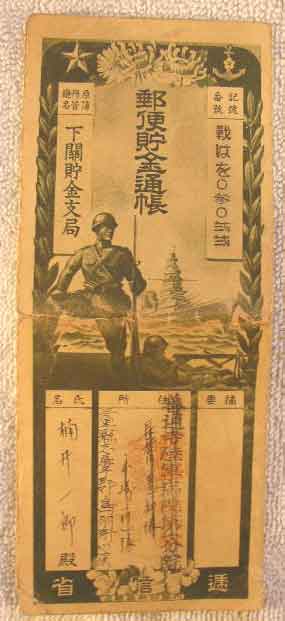

Here is his savings passbook. The centre row of

characters says: yu-bin-cho-kin-tsu-cho

(postal savings passbook). His name and address are down below in handwriting.

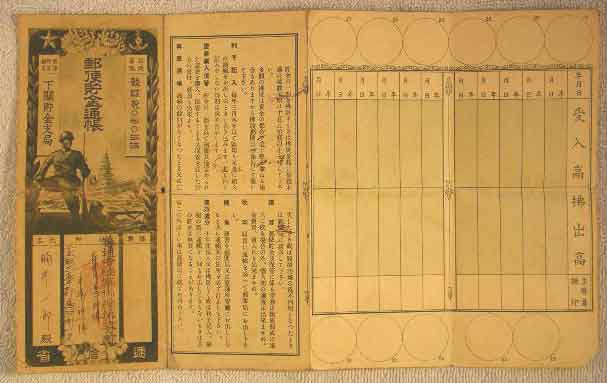

Here it is folded out to show the back.

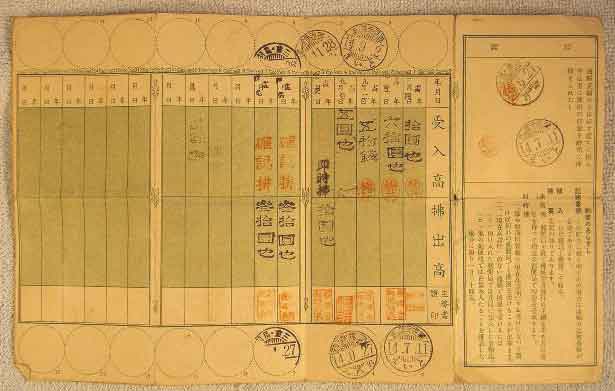

Here is the front side, where you can see his

deposits (top) and withdrawals (bottom). The dates range from July 11, 1939 to

June 27, 1944.

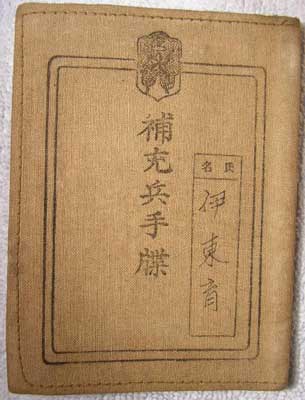

This bag and handbook are named to the same

soldier, a Mr. Iku Ito (surname=Ito). The handbook is a little different than

the one above, as it is labelled ho-ju-jei-te-cho.

Hojuhei means “supplementary

soldier”, or “replacement reservist” (see below), while techo again means “handbook”.

Here is an explanation of the term hojuhei from George Forty’s “Japanese

Army Handbook, 1939-1945”, p.16: “These were men from Classes B-2 and B-3, plus

those in Classes A and B-1 who were not needed to fill the year’s active

service quota [the classes were based on physical condition and height]. They

could be called up to serve anny period of training of not more than 180 days.

After seventeen years and four months, during which time they were subject to

the annual inspection muster, they also entered the 1st National

Army and remained until they reached the age of forty. This reserve was divided

into the 1st and 2nd Conscript Reserves, the distinction

between them being purely decided by the physical qualifications of the

individuals.”

Here is the bag on its own.

This is the back with the usual list of what’s

supposed to go inside.

This is a close-up of the booklet. It’s the

same size as the one shown above. It has Imperial Rescripts and rules for

replacement reservists, as well as some personal records. The crest at the top

is that of the Imperial Reservists’ Association.

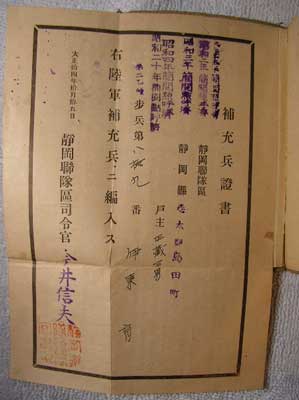

This fold-out is inside the back cover. It is

entitled ho-ju-hei-sho-sho, or

“Replacement reservist certificate”. The purple stamps in the upper right are

dates. They indicate Mr. Ito did roll call (kan-etsu

ten-ko) in Taisho 15, Showa 2, 3 and 4 (1926, 1927, 1928 and 1929), then

again in 1945. That last one must have come as a bit of a shock. He was 40

years old at that time and just at the limit for service age. This was probably

in preparation for the final defense of the home islands against the invasion

that never came due to the surrender.

The second column of printed text says Shizu-oka-ren-tai-ku, Shizuoka

Regimental Area.The third begins Shizu-oka-ken,

The next

column indicates the name of the head of his household (ko-shu): Mr. Mitsuo

Shozo (family name is Shozo).

The next column indicates he was a B-2 class

recruit, and ends in his name. There is some stuff in the middle I have to

figure out yet.

The purple stamp in the lower left gives the

name of the commanding officer (shi-rei-kan)

of the

The back of this fold-out page has a set of

rules or guiding principles (kokoroe)

for reservists.

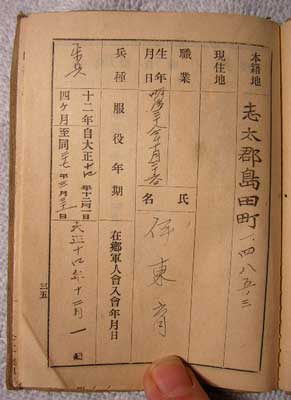

The first column on the right is Mr. Iku’s

address, Shida-gun, Shimada-machi 1-485-3. The short column in the upper middle

is his birth date, October 26, Meiji 38 (1905).

The wide column in the lower middle is his name. The far leftt column

indicates he was eligible to serve for 12 years and four months, from December

1, Taisho 14 (1925) to March 31, Taisho 27 (1938). Actually there never was a

Taisho 27; the Taisho Emperor dies in late 1926 (Taisho 15), so 1938 was

actually known as Showa 13 by the time it came around. Of course, they didn’t

know that when they filled out the document, so they just extrapolated based on

the assumption the then-current emperor would still be around. The bottom left

indicates Mr. Ito entered the Imperial Reservists’ Association on December 1,

Taisho 14 (1925).

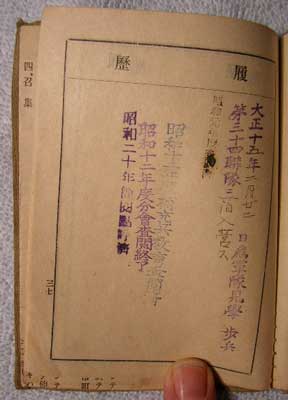

This page is labelled “Personal

History”. The first date on the right is February 22, Taisho 15 (1926). The

rest of that column says ?? gun-tai-ken-gaku

ho-hei (infantry). The second column says dai-san-ju-yon-ren-tai-?-? nyu-ei-su, “entered service in the 34th

regiment…”. The small black column has the date showa gan-nen (Showa 1, i.e. late 1926), then an ink blotch that

mostly obscures the last three characters. The three dates in the middle are

(a) Showa 11 (1936): ho-ju-hei-kyo-iku-sa-etsu-zumi

(completed replacement reservist training inspection);

(b) Showa 12 (1937): bun-kai-sa-etsu-shu-ryo (completed local

chapter inspection); and

(c) Showa 20 (1945): kan-etsu-ten-ko-zumi (completed roll

call).

This next bag has the usual three hokobukuro characters down the centre,

with a box in the lower left. The printed characters at the top of the box say shimei (name), and the handwritten

column of characters identifies the owner as Mr. Kotaro Yamaguchi.

The back has the usual list of stuff

that should go inside, but the interesting bit is in the lower left corner, the

column outside the box.

Here is a close-up. The first six

characters before the triangular symbol say Ku-ru-me-mei-ji-dori.

This bag is very similar to the ones

above except for the colour: it is much less green and more yellow. I have read

that this was characteristic of many of the things Japanese soldiers were

issued, including uniforms, which showed considerable variation from yellowish

to greenish. The owner’s name, handwritten in the box in the lower left, was

Mr. Akira Miyakita. His given name, Akira, is struck out and re-written, as if

written incorrectly the first time. This suggests that it was not the soldier

himself who wrote in his name. Akira is, unfortunately, a name that can be

written with about 200 different characters, so it is not surprising the clerk

got it wrong!

The back has the usual list, however

note that the format of the writing changes from bag to bag so that the number of

characters in the last column (on the left) varies from one to several.

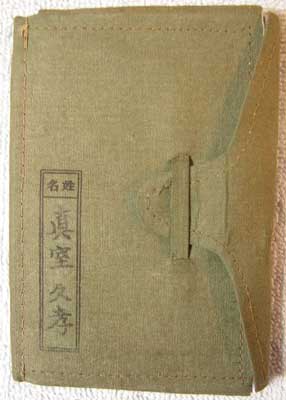

This is another guntai techo

(military handbook). It is quite a bit bigger than the other ones, about 3.5”

by 5” (9cm by 12.5cm). The colour is pretty much the same; some of these photos

turned out a little bluish, but actually they are all greenish.

This is more the shade it actually

is. The back and interior have the same kind f flaps as the others to keep the

book closed.

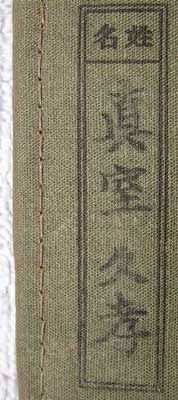

This guy’s name has defeated me so

far. I have not been able to find the first character in his family name, bu it

ends in –muro. His given name could be Hisayuki, although there are several

ways of pronouncing each of the two characters in it.

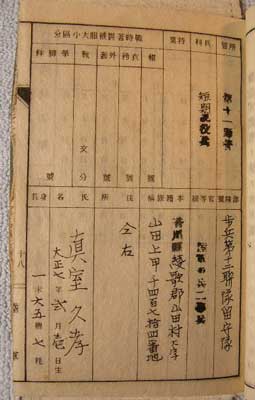

This page has his basic personal

information. In the lower left is his name, date of

birth (February 1, Taisho 7, i.e. 1918), and height (165.7cm, or 5’5”). The

lower right indicates he was in the 12th regiment, home depot force.

His rank was second class private (ni-to-hei).

In the middle is his address in

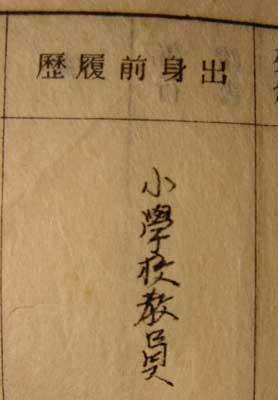

This entry gives his profession before he was

called up: elementary school teacher.

Here is his service history. He

entered service as a short-term serviceman on April 1, 1939 in the 12th

regiment, home depot force, 12th company. The 12th regiment

was based in

The rest of these bags are arranged

in what I believe is a rough chronological order, starting with the earliest

ones. I should emphasize that this ordering is based upon my own speculation, since

I have not been able to find any detailed reference material on the multitude

of variations. Only one bag below can be unambiguously dated (obviously the

bags above with the owner’s records also have dates or at least a period

associated with them). To date the rest of the bags I have relied on rough

heuristics: the nature of the closure, the weight of the material, and the

evolution of the text found on the back of most of these.

My working hypotheses are:

- The drawstring attachment

method evolved towards the style shown above.

- Older bags were generally of

heavier material.

- The text became increasingly

detailed to ensure the proper contents ended up inside.

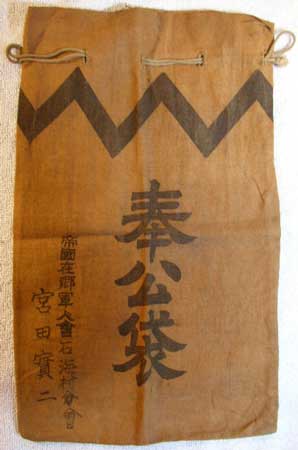

This bag is from the Imperial

Reservists’ Association. The big characters in the far right column are the

familiar hokobukuro (service records

bag), while the slightly smaller column to the left has the name of the

association in Japanese (tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin-kai).

To the left of that is a column that starts with three characters in

handwriting and then three in printed form. They indicate the owner was a local

chapter member (bun-kai-in) in Aka-sa-mura (Akasa village). Note that

this one has a rather unsatisfactorily fragile method of attaching the

drawstring at the top. It has seven small metal rings which were sewn onto the

body of the bag. Four of them are still sewn on and the other three are loose.

This one seems to be made of a denim-weight cotton.

I believe this is the earliest of

the bags based on the following:

1. The

method of attaching the drawstring using rings is inherently weak and was

probably abandoned for the other methods used below. It seems unlikely that the

superior methods would have been abandoned for this poor design.

2. The

material is quite heavy weight.

3. The

pocket represents a design luxury that would probably have been dropped for

ease of manufacture.

4. There is

no text on the back. I hypothesize that the text evolved and became more

specific over time to make sure people actually put the right stuff in the

bags.

Here is the back. It has no list and you can

faintly see the outline of a pocket inside.

Here is a shot of that pocket, which

has a button to close it. The button is made of a very corroded kind of metal

of some sort. I checked carefully and there is nothing in the pocket. However,

it is about the right size for a guntai

techo (soldier’s handbook).

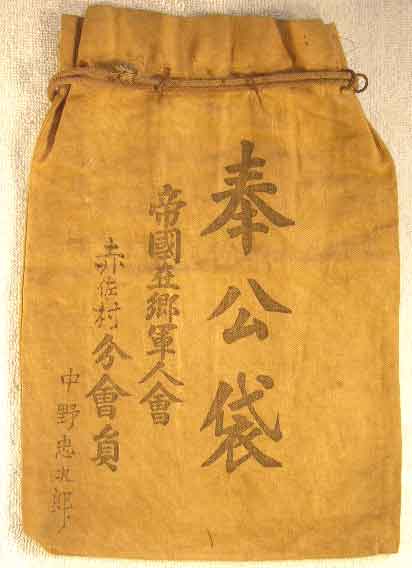

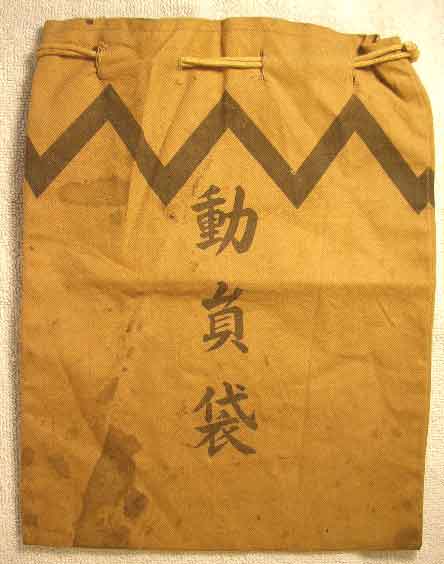

This is another bag of the same basic type, but

it is marked do-in-bukuro, meaning

“mobilization bag”. As you can see, the drawstring is attached in a different

way: threaded through slots rather than hemmed into a channel along the top as

in the ones above. The material is also quite a bit heavier. It seems to be

cotton, almost like a light canvas, approximately the weight of denim.

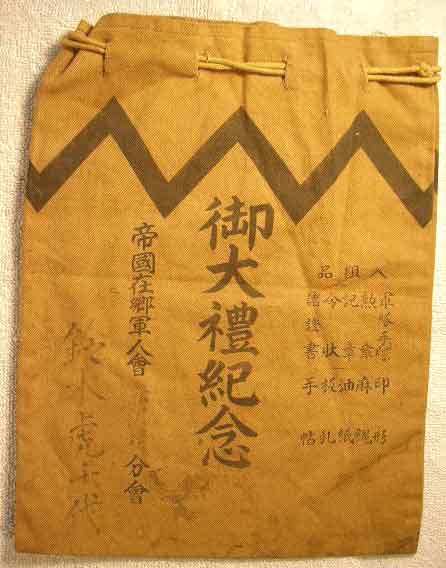

The back suggests that this bag is from about

1928. The clue is the central row of characters. It says gyo-tai-rei-ki-nen, or “commemorating the imperial enthronement”.

Emperor Hirohito’s enthronement took place in late 1928, two years after he

actually became emperor. To the left of the central column is another row of

printed characters that says tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin-kai,

or Imperial Reservists’ Association. There are close-ups below of the left and

right sides.

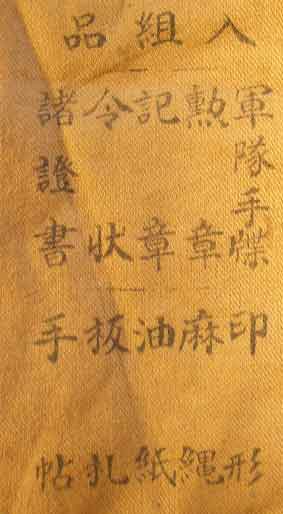

This is a close-up of the printing on the right

side of the central column of characters. The top row reads from right to left:

iri-kumi-hin, or “contents”. The

items to be put inside are listed in columns, each read top to bottom (part of

the fun of reading old stuff in Japanese is figuring out which way to read it).

From right to left, the columns are: gun-tai-te-cho

(soldier’s handbook; see example above); kun-sho

(decorations); kisho (medals); rei-jo (call-up order); sho-sho-sho (“various documents”; yes,

the three different characters are all read sho).

The last two rows confused me at first; althought

they are quite far apart, they are actually supposed to be read as vertical

columns from right to left: in-gyo

(seal; used for stamping one’s name); asa-nawa

(hemp cord); abura-gami (oiled paper,

also pronounced yu-shi); ita-fuda

(name plate; might also be pronounced han-satsu); te-cho (notebook). Most of these items were for wrapping up one’s

civilian clothes when called up.

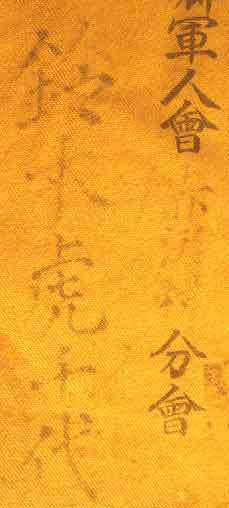

Here is a close-up of the handwritten part on

the left below “Imperial Reservists’ Association”. The very faint column on the

right gives the location of the bun-kai,

or local chapter: Aka-zawa-mura (mura means village). To the left of that

is the man’s name: Suzuki Torachishiro.

The surname Suzuki is for sure, but

that last name is pretty unusual, so I can’t guarantee the pronunciation 100%.

The tora part in it means tiger.

I am putting this one next because

it has the same style of drawstring, i.e. it goes through small slots in the

bag rather than a hemmed-in channel. It is made of a similar weight of cloth,

but the shape is somewhat different. It is about ½” (12mm) narrower and two

inches (5cm) longer than the bag above. It has the usual hokobukuro in the centre and over in the lower left, the usual teikoku zaigo gunjinkai. The handwriting

below that indicates it is from the Ishi-umi-mura-bun-kai

(Ishiumi village local chapter). The owners name was Mr. Miyata. His given name

is an unusual one not in my name book, but it may have been pronounced

Sane-kazu.

Here is the back. As you can see,

there is far more stuff listed on the back of this one than the one above.

Besides listing things it has various clarifying instructions that I will

translate later.

Here’s a close-up of all that text.

To the lower left of the text box is

a column of characters that give the supplier’s name and location: Hime-ji-shi-hon-machi (

This seems to be another

older bag from the Imperial Reservists’ Association. The material is heavier,

but it has the same drawstring style as the later ones. The crest at the top is

the symbol of the Imperial Reservists’ Association and the three large

characters are ho-ko-bukuro.

Here is the back.

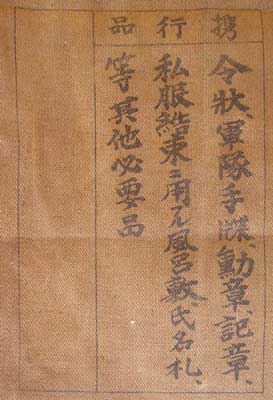

The back has a list of contents (kei-ko-hin, literally, “things to carry

along”). The first column on the right is rei-jo,

gun-tai-te-cho, kun-sho, ki-sho, or “orders, military handbook,

decorations, campaign medals”. The second and third columns continue, shi-fuku-kes-soku-ni-yo-su-ru-fu-ro-shiki,

shi-mei-satsu, nado-sono-ta-hitsu-yo-hin: a wrapping cloth (furoshiki) and

name tag, etc. to bundle up civilian clothes and other necessary

things.

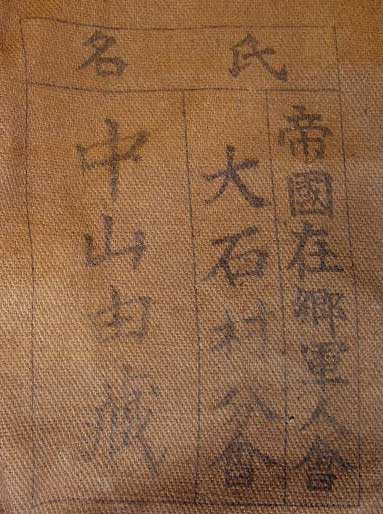

This close-up of the name box from

the lower left corner of the front of the bag has three columns under the main

heading shi-mei (name). The one on

the far right is tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin-kai,

“Imperial Reservists’ Association”. The middle row is the location, o-ishi-mura-bun-kai, “Oishi village branch

chapter”. The left column has the soldier’s name, Nakayama Yuzo

(surname=Nakayama).

This is another reservist’s bag,

also an older one, I think. The crest at the top is the symbol of the Imperial

Reservists’ Association. The column on the far right says tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin, “Imperial Reservist”. The three characters

in the middle are the usual ho-ko-bukuro.

The box is shown in close-up below.

The back has a list of what is to go

inside. The title at the far right says o-sho-no-ba-ai-ni-kei-ko-su-ru-hin,

“things to take along when called up”. The numbers one to four head the

remaining columns (number one has two columns).

- rei-jo, gun-tai-te-cho, kun-sho, ki-sho, teki-nin-sho-sho,

sotsu-gyo-sho-sho, shu-gyo-sho-sho, in-sho: orders, military handbook, decorations,

campaign medals, certificates of qualification, graduation certificates,

certificates of study, name stamp.

- cho-kin-tsu-cho: savings passbook.

- shi-fuku-kes-soku-yo, fu-ro-shiki,

tsutsumi-gami, asa-nawa, moku-satsu: wrapping cloth (furoshiki),

wrapping paper, hemp cord, wooden name tag.

- o-sho-ryo-ko-hitsu-yo-hin-oyobi-nichi-yo-hin:

things needed for the call-up journey or for daily use.

The box in the lower left of the front is shown

here in close-up. The box is headed shi-mei (name). The right column says tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin-kai, “Imperial

Reservists’ Association”. The middle column says ka-ko-gawa bun-kai,

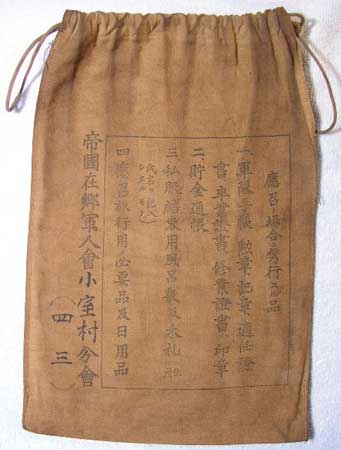

Below the crest of the Imperial Reservists’

Association are the three characters ho-ko-bukuro.

This one is also made of fairly heavy material. It came with a booklet from the

local chapter of the Association.

The list of contents on the back of

this one is quite similar to the one above, but with a little extra in brackets

at the end of point three. At the left, outside of the box, the long column

begins with tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin-kai,

“Imperial Reservists’ Association”. The local chapter (bun-kai) name is written in by hand: ko-muro-mura (Komuro village).

The kanji for the number 43 appear in the brackets at the far left. Since there

is no name on the bag, this might be the owner’s member number, perhaps.

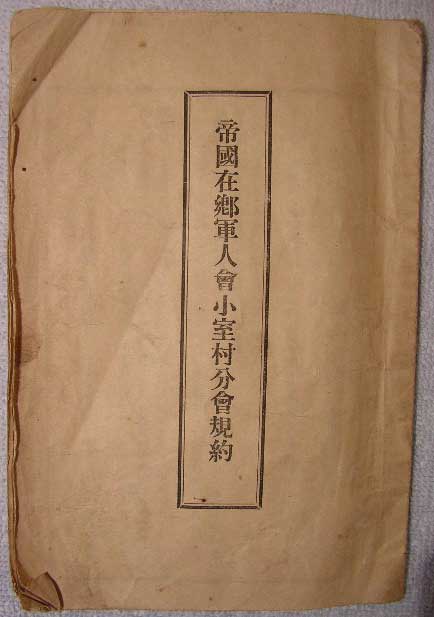

This is the booklet that came with

the bag. The central column of characters reads: tei-koku-zai-go-gun-jin-kai-ko-muro-bun-kai-ki-yaku, Rules of the

Komuro Local Chapter of the Imperial Reservists’ Association”.

This bag is the same but with no name marked in

it.

Here’s the back.

Click here to go back to the Japanese Military

Bags page: Japanese Military Bags

Click here to go back to the Other Militaria

page: Teri's Japanese

Handgun Website: Other Japanese Militaria

Click here to go back to the main page: Teri’s Japanese Handgun Website

Last updated: November 6, 2004. All contents

are copyright Teri unless otherwise specified and may not be used elsewhere in

any form without prior permission.